Reflections on Space

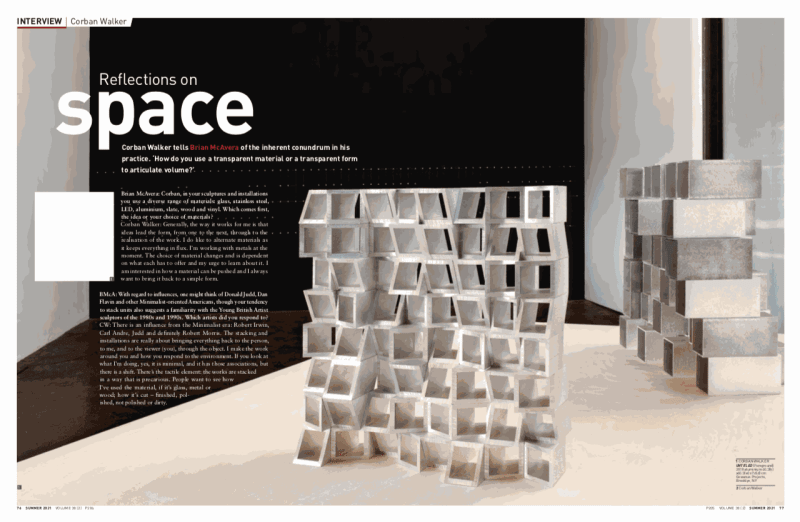

Corban Walker tells Brian McAvera of the inherent conundrum in his practice. ‘How do you use a transparent material or a transparent form to articulate volume?’

Brian McAvera: Corban, in your sculptures and installations you use a diverse range of materials: glass, stainless steel, LED, aluminium, slate, wood and vinyl. Which comes first, the idea or your choice of materials?

Corban Walker: Generally, the way it works for me is that ideas lead the form, from one to the next, through to the realisation of the work. I do like to alternate materials as it keeps everything in flux. I’m working with metals at the moment. The choice of material changes and is dependent on what each has to offer and my urge to learn about it. I am interested in how a material can be pushed and I always want to bring it back to a simple form.

BMcA: With regard to influences, one might think of Donald Judd, Dan Flavin and other Minimalist-oriented Americans, though your tendency to stack units also suggests a familiarity with the Young British Artist sculptors of the 1980s and 1990s. Which artists did you respond to?

CW: There is an influence from the Minimalist era: Robert Irwin, Carl Andre, Judd and definitely Robert Morris. The stacking and installations are really about bringing everything back to the person, to me, and to the viewer (you), through the object. I make the work around you and how you respond to the environment. If you look at what I’m doing, yes, it is minimal, and it has those associations, but there is a shift. There’s the tactile element: the works are stackedin a way that is precarious. People want to see how I’ve used the material, if it’s glass, metal orwood; how it’s cut – finished, polished, not polished or dirty.

AS A MATERIAL, GLASS CAN TRANSMIT AND REFLECT LIGHT AND ARTICULATE A FORM THAT FLOATS

The stacks create a space, a theatre, where you and the work convene and explore what’s going on. Brânçusi says simplic- ity is complexity resolved, and that’s true, I think. Then again, it makes me think of Giacometti, and how he transformed sculptural form entirely, by paring it down to the absolute minimum; yet he still managed to exhibit every emotion and movement in his sculpture.

BMcA: Growing up, how did your height (just over four foot) shape your view of the world and your relationship to it?

CW: My height had a big impact on how I came to terms with the world. I remember realising what was going on (that I wasn’t getting any taller) when I noticed that my younger sister, Ciannait, was overtaking me. My mother held the idea that there was no need to worry about my height until it became a problem. Later on, however, it was difficult to come to terms with it. While I felt that there was no reason why I couldn’t participate as well as anybody else, it was dif- ficult for me to do so – particularly in activities like sports. An orthopaedic doctor, Dr Sugars, gave me special shoes to wear to prevent any further disability. I was top heavy and he had to make sure that my legs were as strong as possible to support my body weight.Some people do have a go at you in the streets. It makes you feel vulnerable and exposed. It’s like having a spotlight on you. It’s embarrassing and frustrating and it can make you angry and humiliated. After fifty-odd years of this, you take it as it comes.

BMcA: You were at NCAD from 1987 to 1992 and have previously remarked that the most interesting aspects of that education came from visiting artists such as Dorothy Cross, Willie Doherty, Bill Viola, Nancy Spero, Leon Golub, James Coleman, Bill Woodrow and Nigel Rolfe. What kind of work were you producing at college?

CW: I was initially turned down for the Foundation Course at NCAD. I then applied for Fine Art and I was accepted on the strength of the interview. It took me a while to figure out what I was interested in. Having had wide influences from my parents, peers and friends in terms of what art was, it was difficult for me to concentrate. Thanks to Willie Doherty, who set me to looking at myself, I turned my attention to my own body, to scale, and how that related to what I was doing. I started doing works about measure.

BMcA: What was it like attending NCAD in the 1980s?

CW: At that time Dublin was in the grip of a heroin epidemic. The back gate of NCAD gave onto flats that were a hotbed of heroin abuse and were frequently raided by the gardaí. There was gang violence – it was a volatile environment. In the college, there were problems with tutors being absent or in the pub. But the visiting artists brought an extraordi- nary energy to the place and the students benefited greatly. I learnt a lot from some of the other students there at the same time, too, like the late Maurice O’Connell, Gerard Byrne and Clare Langan. You could do anything you wanted. We were trying to embrace a new era. A lot of things were changing in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

It was frustrating though. The college had no money at the time. But Noel Sheridan, the director, was fantastic, forever encouraging students. There were no paints, no sculpture materials. But he kept a programme going for visiting art- ists to come to lecture and give tutorials. There was also a bit of friction between the students and the full-time staff. It felt like the college could close at any moment!

BMcA: In 1994, you had your first solo show, your sculp- ture installation Latitude, at the City Arts Centre in Dublin. Using galvanised steel wire, it was where you first elaborated what Medb Ruane called the ‘self-styled “Corbanscale”’. Tell us about it.

CW: ‘Corbanscale’ is the rule I still work with. It’s taking the Vitruvian Man and translating it to my height and measure as opposed to the average male height of six feet. It equates back to the golden ratio (1: 1.618)’. Latitude was an installation of 25 bands of galvanised steelwire, evenly spaced and stretching across the room within a rectangular form. Entering the gallery, fine wire was barely visible to the viewer until they walked up very close to the intervention in the space, where they were confronted by Latitude and had to duck down to pass and continue their journey into the room. The bottom line of the steel wire was 129 cm above floor level (my height) with the top line at 60 cm above that. Essentially, the work asks the viewer to reevaluate his or her relationship with the space and how they articulate their surroundings. I can walk under the wireuninterrupted. It was an introduction to ‘Corbanscale’ and a discussion about my perception of scale and how I nav- igate our surroundings in an environment designed for an alternative human measure (Latitude is in the collection of the Guggenheim Museum, New York).

BMcA: Ten years later you moved to New York. What effect did the city of skyscrapers have on your work?

CW: I had a show in New York at the Pace Gallery in 2000. I relocated there in December 2004 and within a few months of arriving they took me on as a gallery art- ist. Pace Gallery were taking on new, younger artists and I was part of that wave. I set up studio and they worked with me and supported me. The scale of the city with its skyscrapers was exhilarating. It empowered me to develop what I was doing with scale. I felt more at ease there than in a semi in Ireland. It’s the scale of how things are done in New York: more funding, more people to help realise projects, more access to research. That was exciting: to be able to use those sorts of resources. Going from Dublin to a studio in New York where I had two or three people helping me was a huge transformation.

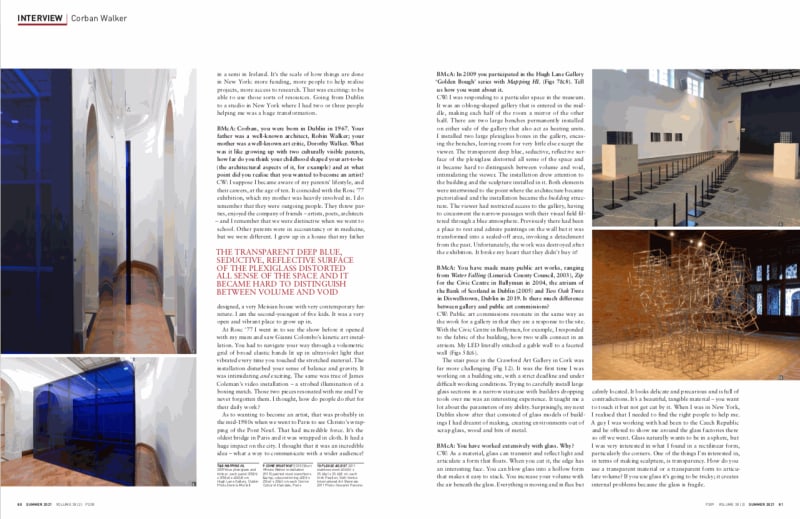

BMcA: Corban, you were born in Dublin in 1967. Your father was a well-known architect, Robin Walker; your mother was a well-known art critic, Dorothy Walker. What was it like growing up with two culturally visible parents, how far do you think your childhood shaped your art-to-be(the architectural aspects of it, for example) and at what point did you realise that you wanted to become an artist?

CW: I suppose I became aware of my parents’ lifestyle, and their careers, at the age of ten. It coincided with the Rosc ’77 exhibition, which my mother was heavily involved in. I do remember that they were outgoing people. They threw par- ties, enjoyed the company of friends – artists, poets, architects – and I remember that we were distinctive when we went to school. Other parents were in accountancy or in medicine, but we were different. I grew up in a house that my father designed, a very Meisian house with very contemporary fur- niture. I am the second-youngest of five kids. It was a very open and vibrant place to grow up in. At Rosc ’77 I went in to see the show before it opened with my mum and saw Gianni Colombo’s kinetic art instal- lation. You had to navigate your way through a volumetric grid of broad elastic bands lit up in ultraviolet light that vibrated every time you touched the stretched material. The installation disturbed your sense of balance and gravity. It was intimidating and exciting. The same was true of James Coleman’s video installation – a strobed illumination of a boxing match. Those two pieces resonated with me and I’ve never forgotten them. I thought, how do people do that for their daily work?

As to wanting to become an artist, that was probably in the mid-1980s when we went to Paris to see Christo’s wrap- ping of the Pont Neuf. That had incredible force. It’s the oldest bridge in Paris and it was wrapped in cloth. It had a huge impact on the city. I thought that it was an incredible idea – what a way to communicate with a wider audience!

BMcA: In 2009 you participated in the Hugh Lane Gallery ‘Golden Bough’ series with Mapping HL (Figs 7&8). Tellus how you went about it.

CW: I was responding to a particular space in the museum. It was an oblong-shaped gallery that is entered in the mid- dle, making each half of the room a mirror of the other half. There are two large benches permanently installed on either side of the gallery that also act as heating units. I installed two large plexiglass boxes in the gallery, encas- ing the benches, leaving room for very little else except the viewer. The transparent deep blue, seductive, reflective sur- face of the plexiglass distorted all sense of the space and it became hard to distinguish between volume and void, intimidating the viewer. The installation drew attention to the building and the sculpture installed in it. Both elements were intertwined to the point where the architecture became pictorialised and the installation became the building struc- ture. The viewer had restricted access to the gallery, having to circumvent the narrow passages with their visual field fil- tered through a blue atmosphere. Previously there had been a place to rest and admire paintings on the wall but it was transformed into a sealed-off area, invoking a detachment from the past. Unfortunately, the work was destroyed after the exhibition. It broke my heart that they didn’t buy it!

BMcA: You have made many public art works, ranging from Water Falling (Limerick County Council, 2003), Zip for the Civic Centre in Ballymun in 2004, the atrium of the Bank of Scotland in Dublin (2005) and Two Oak Trees in Diswellstown, Dublin in 2019. Is there much difference between gallery and public art commissions?

CW: Public art commissions resonate in the same way as the work for a gallery in that they are a response to the site. With the Civic Centre in Ballymun, for example, I responded to the fabric of the building, how two walls connect in an atrium. My LED literally stitched a gable wall to a faceted wall. The stair piece in the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork was

far more challenging. It was the first time I was working on a building site, with a strict deadline and under difficult working conditions. Trying to carefully install large glass sections in a narrow staircase with builders dropping tools over me was an interesting experience. It taught me a lot about the parameters of my ability. Surprisingly, my next Dublin show after that consisted of glass models of build- ings I had dreamt of making, creating environments out of scrap glass, wood and bits of metal.

BMcA: You have worked extensively with glass. Why?

CW: As a material, glass can transmit and reflect light and articulate a form that floats. When you cut it, the edge has an interesting face. You can blow glass into a hollow form that makes it easy to stack. You increase your volume with the air beneath the glass. Everything is moving and in flux but calmly located. It looks delicate and precarious and is full of contradictions. It’s a beautiful, tangible material – you want to touch it but not get cut by it. When I was in New York, I realised that I needed to find the right people to help me. A guy I was working with had been to the Czech Republic and he offered to show me around the glass factories there so off we went. Glass naturally wants to be in a sphere, but I was very interested in what I found in a rectilinear form, particularly the corners. One of the things I’m interested in, in terms of making sculpture, is transparency. How do you use a transparent material or a transparent form to articu- late volume? If you use glass it’s going to be tricky; it creates internal problems because the glass is fragile.

BMcA: In 2011 you represented Ireland at the Venice Bien- nale. In terms of adapting your work to the specifics of Venice, how did you go about it?

CW: I was based in New York then and I built the main part of the show in my studio as a trial run. So we knew what it was going to look like and how to put it together. When I saw the space, I thought, ‘pretty challenging’. There were so many things beyond my control: the terracotta floor tiles and the bits added to the space over the centuries. There was also an in-between space. There was a garden off a narrow alleyway at one end and the canal at the other.I didn’t want to bring glass to Venice, for obvious rea- sons – the history of Venetian Murano glass. That would have been counterproductive. There was also a glass wall in the middle of this busy, difficult space so I thought, ‘Let’s use the transparency that’s already there and build on it.’ I made three works that were translucent or light reflecting and I had the idea of the viewer walking through an instal- lation where you could enter the transient space either by boat from the canal or by foot through a garden. The main piece, Please Adjust, was a precarious stainless-steel towering assemblage, mirroring the dire economic fallout that Ireland was experiencing at the time (Fig 10). The vinyl pieces on the existing glass deliberately confused viewers’ ability to orientate themselves in the space. It was an ambiguous sit- uation for very uncertain times. Getting around Venice had its own challenges, too – being squished like a sardine on the Vaporetto. But it’s Venice and you are distracted by the beauty and the architecture – it’s so extraordinary.

BMcA: In 2018 you exhibited at the Centre Culturel Irlan- dais in Paris and in New York. What kind of work did you produce for each?

CW: I was recovering after a major spinal operation and the exhibitions were a way to come to terms with that by immers- ing myself in my art. ‘Come What May’ was the title of the Paris show. The main piece was a double row of stanchions (Fig 9). In a museum show, I often find that stanchions can obstruct the artwork quite considerably. Once again, with the lines of stanchions, I was directing people through the space. There were other works in aluminium and stain- less-steel tubing, stacked into a cubic grid, open, closed and overlaid, so that you had a fluctuating, intermittent view. The New York show was six months later. It took place in a friend’s large studio that had a metal shop in it. The back of the studio was used as a gallery space. He invited artists to use the metal shop and then show work in the gallery. I made stacks or maquettes out of aluminium tubing. It was a more intimate piece.

BMcA: You now live in Cork and are preparing for a show at the Crawford Art Gallery next year. How are prepara- tions going for you?

CW: I came back to Ireland and had to find my feet. During a heatwave in the summer of 2018, I came to Cork, did a month’s residency at the National Sculpture Factory and fell in love with the place. I now have a studio there which is fully equipped and very affordable. The Crawford have invited me to exhibit in the origi- nal Crawford building just before it closes for renovations next year. I am going to respond to the architecture of the building and to particular works in the collection on the ground and first floors. I want to create a book-object monograph on the 21st-century work, a condensed toolkit with which to explore the work. I will also show work made in the States that has not been seen in Ireland before.

BMcA: In 2011 Brian O’Doherty referred to an early art- work of yours as being ‘a small step made to accommodate his size. It gave notice that his redesign of the world would fit his own corpus, not necessarily yours or mine.’ Is this a fair assessment of your current position?

CW: Yeah. Sure. Literally! Essentially what I’ve been doing throughout my oeuvre is to enable the viewer to be the work, putting them into a situation where they are hyper-aware of what they are looking at, of how they navigate a space, of how they are a part of the installation. That’s been the case since 1994 – and always will be. It’s a level of engagement with the work that fluctuates. Some of my pieces are more about temporary entrapment, others about viewing from a safe distance. When people become aware of something within themselves being altered, it knocks them off balance and they become confused and frustrated. If I can alter their behaviour, make them aware of what is happening to their visual field, a different way of existing temporarily – well, that’s my existence on a daily basis! It’s not my intention to manipulate people for the sake of it. I’m facilitating the viewer while trying to make them more conscious and aware of the lack of inclusiveness in society. Growing up in the modern mews my father designed where much of the interior wall space was made of glass that looked out to a Japanese garden – a glasshouse, if you will – I could see everything. Nothing was obstructed. Now, out of that house, I’m constantly being obstructed. In many ways, the influence of my father’s work is still present in a lot of my installations.