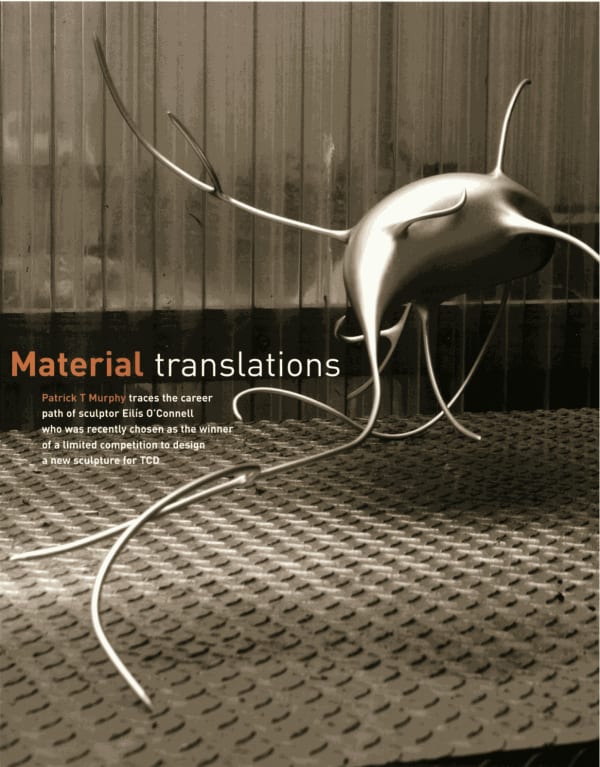

Patrick T Murphy traces the career path of sculptor Eilís O’Connell who was chosen as the winner of a limited competition to design a new sculpture for TCD

In the 1984 edition of Rosc, Irish artists were included in the selection for the very first time since the exhibition’s inception in 1967. Perhaps this signified the maturation of contemporary art practice in Ireland and its concurrency with art-making internationally. Or, maybe it was a little positive discrimination to deflect much criticism in previous years of the lack of Irish participation in the show. There was some dissension amongst the panel of jurors about this decision, with one, Fritz Beck from Holland resigning in protest at the move. The youngest of the ten Irish artists included in that year was Eilís O’Connell, then just thirty. Her largest exhibited piece, a tumbling steel spiral, adorned with fibrous paper and feather was entitled Beat them at their own game and indeed for the past three decades that is exactly what she has been up to!

O’Connell’s work of the 1980s is characterized by a thorough investigation into materials, their qualities and their cultural values. She also explored many different patinations moving away from the primaries and blacks of the international style of the time to subtle hues of earthy maroons and evocative blues. She designed some objects for the floor, others for the wall. Composites of materials were tested, handmade paper danced with steel, wire and rope interconnected space and line. She was also intensely interested in pushing the independent object into a relationship with other objects to establish a group dynamic that would amplify and extend the impact of the sculpture in both its formalism and its affect. There was an anthropological sense to her pieces, some shamanistic, while others seemed to be fragments of implements whose purpose was lost in time.

O’Connell’s art received a great deal of acclaim in Ireland during that decade which lead to awards such as the Guinness Peat Emerging Artists Award, residencies in Rome, at the British School (though raised in Cork she was born in Derry), followed by New York and then onto the Delfina Studios in London where a two-year residency was to turn into a fifteen-year stay in the British capital. In 1987, she succeeded in securing one of the largest public commissions in these islands for a site in Kinsale. Unveiled in 1988 her Great Wall of Kinsale was to create public controversy aesthetically and on health and safety issues. In the end the surface was painted to an easily maintained grey, rails were added to stop climbing and skate boarding, all without consultation. The artist was badly stung and perhaps such official vandalism contributed to her decision to stay on in London. During those years her reputation in Ireland receded from a wider awareness to a few individuals that followed her solid climb to recognition as an important sculptor in Britain.

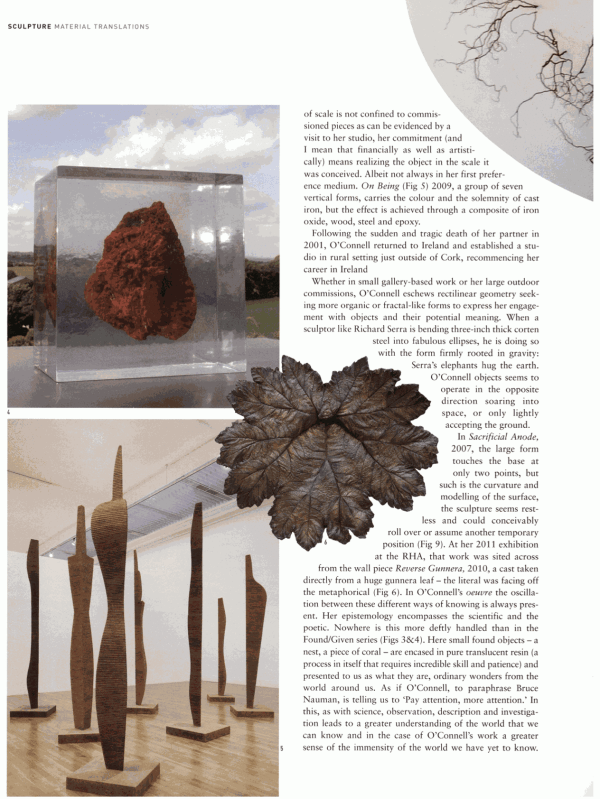

O’Connell received a number of major public commissions during her time there. Amongst the most notable were; Secret Station, 1992 for the Cardiff Bay Arts Trust at the Gateway, Cardiff, Vowel of Earth Dreaming its Root, for the London Docklands Development Corporation at Marsh Wall, The Isle of Dogs, London. And Pero, a footbridge, a rolling bascule bridge designed in collaboration with Ove Arup Engineers, London, 1999. These works allowed O’Connell to become fluent in scale, some works were twelve-metres high; another fifty-four-metres long. To the basic sculptural vocabulary of bronze, stone and steel O’Connell mastered fibre optics and even steam generation. It’s worth saying that O’Connell’s exploration of scale is not confined to commissioned pieces as can be evidenced by a visit to her studio, her commitment (and I mean that financially as well as artistically) means realizing the object in the scale it was conceived. Albeit not always in her first preference medium. On Being (Fig 5) 2009, a group of seven vertical forms, carries the colour and the solemnity of cast iron, but the effect is achieved through a composite of iron oxide, wood, steel and epoxy.

In O’Connell’s oeuvre the oscillation between these different ways of knowing is always present. Her epistemology encompasses the scientific and the poetic.

Following the sudden and tragic death of her partner in 2001, O’Connell returned to Ireland and established a studio in rural setting just outside of Cork, recommencing her career in Ireland.

Whether in small gallery-based work or her large outdoor commissions, O’Connell eschews rectilinear geometry seeking more organic or fractal-like forms to express her engagement with objects and their potential meaning. When a sculptor like Richard Serra is bending three-inch thick corten steel into fabulous ellipses, he is doing so with the form firmly rooted in gravity: Serra’s elephants hug the earth. O’Connell objects seems to operate in the opposite direction soaring into space, or only lightly accepting the ground.

In Sacrificial Anode, 2007, the large form touches the base at only two points, but such is the curvature and modelling of the surface, the sculpture seems restless and could conceivably roll over or assume another temporary position (Fig 8). At her 2011 exhibition at the RHA, that work was sited across from the wall piece Reverse Gunnera, 2010, a cast taken directly from a huge gunnera leaf – the literal was facing off the metaphorical (Fig 6). In O’Connell’s oeuvre the oscillation between these different ways of knowing is always present. Her epistemology encompasses the scientific and the poetic. Nowhere is this more deftly handled than in the Found/Given series (Fig 3). Here small found objects – a nest, a piece of coral – are encased in pure translucent resin (a process in itself that requires incredible skill and patience) and presented to us as what they are, ordinary wonders from the world around us. As if O’Connell, to paraphrase Bruce Nauman, is telling us to ‘Pay attention, more attention.’ In this, as with science, observation, description and investigation leads to a greater understanding of the world that we can know and in the case of O’Connell’s work a greater sense of the immensity of the world we have yet to know.

O’Connell eschews rectilinear geometry seeking more organic or fractal-like forms to express her engagement with objects and their potential meaning

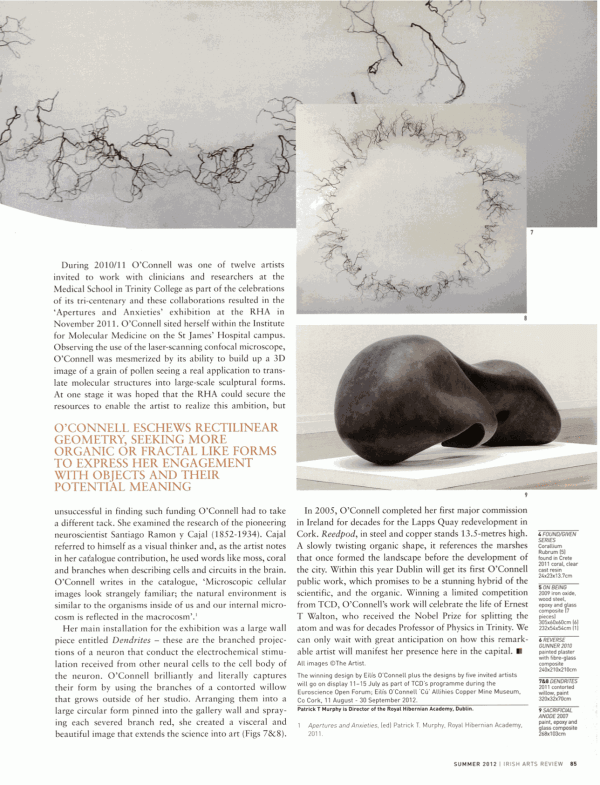

During 2010/11 O’Connell was one of twelve artists invited to work with clinicians and researchers at the Medical School in Trinity College as part of the celebrations of its tri-centenary and these collaborations resulted in the ‘Apertures and Anxieties’ exhibition at the RHA in November 2011. O’Connell sited herself within the Institute for Molecular Medicine on the St James’ Hospital campus. Observing the use of the laser-scanning confocal microscope, O’Connell was mesmerized by its ability to build up a 3D image of a grain of pollen seeing a real application to translate molecular structures into large-scale sculptural forms. At one stage it was hoped that the RHA could secure the resources to enable the artist to realize this ambition, but unsuccessful in finding such funding O’Connell had to take a different tack. She examined the research of the pioneering neuroscientist Santiago Ramon y Cajal (1852-1934). Cajal referred to himself as a visual thinker and, as the artist notes in her catalogue contribution, he used words like moss, coral and branches when describing cells and circuits in the brain. O’Connell writes in the catalogue, ‘Microscopic cellular images look strangely familiar; the natural environment is similar to the organisms inside of us and our internal microcosm is reflected in the macrocosm'(1).

Her main installation for the exhibition was a large wall piece entitled Dendrites – these are the branched projections of a neuron that conduct the electrochemical stimulation received from other neural cells to the cell body of the neuron. O’Connell brilliantly and literally captures their form by using the branches of a contorted willow that grows outside of her studio. Arranging them into a large circular form pinned into the gallery wall and spraying each severed branch red, she created a visceral and beautiful image that extends the science into art (Fig 7).

In 2005, O’Connell completed her first major commission in Ireland for decades for the Lapps Quay redevelopment in Cork. Reedpod, in steel and copper stands 13.5-metres high. A slowly twisting organic shape, it references the marshes that once formed the landscape before the development of the city. Within this year Dublin will get its first O’Connell public work, which promises to be a stunning hybrid of the scientific, and the organic. Winning a limited competition from TCD, O’Connell’s work will celebrate the life of Ernest T Walton, who received the Nobel Prize for splitting the atom and was for decades Professor of Physics in Trinity. We can only wait with great anticipation on how this remarkable artist will manifest her presence here in the capital.

All images ©The Artist.

Patrick T Murphy is Director of the Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin.

1 Apertures and Anxieties, (ed) Patrick T. Murphy, Royal Hibernian Academy, 2011.

First published in the Irish Arts Review Vol 29, No 2, 2012