Irish Artists in the UK: Eilís O’Connell’s elemental and timeless sculptural installations in London by Sue Hubbard

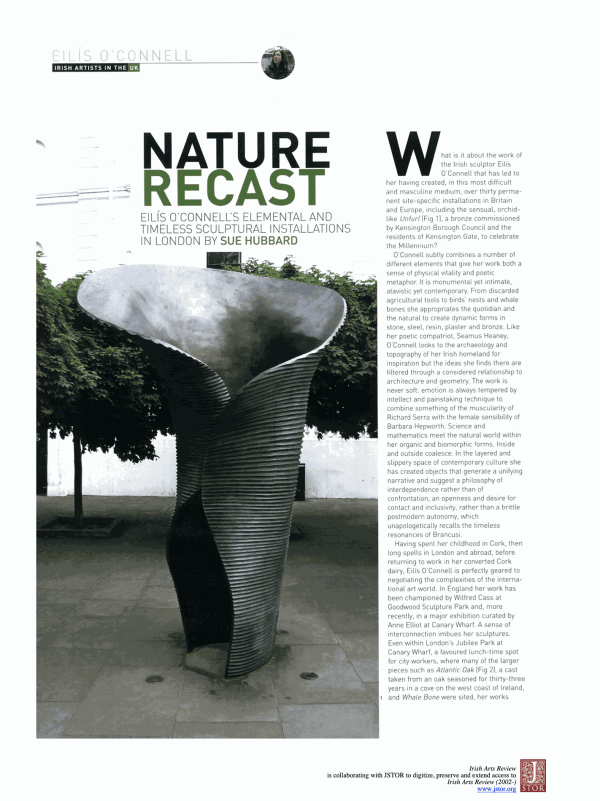

What is it about the work of the Irish sculptor Eilís O’Connell that has led to her having created, in this most difficult and masculine medium, over thirty permanent site-specific installations in Britain and Europe, including the sensual, orchid-like Unfurl (Fig 1), a bronze commissioned by Kensington Borough Council and the residents of Kensington Gate, to celebrate the Millennium?

O’Connell subtly combines a number of different elements that give her work both a sense of physical vitality and poetic metaphor. It is monumental yet intimate, atavistic yet contemporary. From discarded agricultural tools to birds’ nests and whale bones she appropriates the quotidian and the natural to create dynamic forms in stone, steel, resin, plaster and bronze. Like her poetic compatriot, Seamus Heaney, O’Connell looks to the archaeology and topography of her Irish homeland for inspiration but the ideas she finds there are filtered through a considered relationship to architecture and geometry. The work is never soft: emotion is always tempered by intellect and painstaking technique to combine something of the muscularity of Richard Serra with the female sensibility of Barbara Hepworth. Science and mathematics meet the natural world within her organic and biomorphic forms. Inside and outside coalesce. In the layered and slippery space of contemporary culture she has created objects that generate a unifying narrative and suggest a philosophy of interdependence rather than of confrontation, an openness and desire for contact and inclusivity, rather than a brittle postmodern autonomy, which unapologetically recalls the timeless resonances of Brancusi.

In the layered and slippery space of contemporary culture she has created objects that generate a unifying narrative

Having spent her childhood in Cork, then long spells in London and abroad, before returning to work in her converted Cork dairy, Eilís O’Connell is perfectly geared to negotiating the complexities of the international art world. In England her work has been championed by Wilfred Cass at Goodwood Sculpture Park and, more recently, in a major exhibition curated by Anne Elliot at Canary Wharf. A sense of interconnection imbues her sculptures. Even within London’s Jubilee Park at Canary Wharf, a favoured lunch-time spot for city workers, where many of the larger pieces such as Atlantic Oak (Fig 2), a cast taken from an oak seasoned for thirty-three years in a cove on the west coast of Ireland, and Whale Bone were sited, her works eemed to preserve within them a sense of memory and place that remains embedded deep within their fabric, even in their unfamiliar urban setting. It is this primordial quality that connects the viewer, often unconsciously, to a sense of something elemental. Thus O’ Connell manages to tap into a sense of common origin within the fragmentation of the city. Sacrificial Anode, cast especially in bronze for this exhibition, now has a permanent place in the park after having been bought by Canary Wharf (Fig 5). The wonderfully poetic title, which suggests a metaphor of corrosion and decay is, in fact, a metallurgical term. An anode attached to a metal object, such as a boat or underground tank, is put there to inhibit the object’s corrosion. The anode electrolytically decomposes while the object remains free of damage. That Eilís O’Connell was trained, unusually for a woman, in the tradition of working with industrial materials has provided a fruitful extension to the more feminine side of her sculptural language, to her relationship with intimate spaces, and to the curves and folds of the body.

In counterpoint to her scaled-up, monumental works the lobby at Canary Wharf included a series of clear resin works. Using found objects and those given to her by friends – a vulture’s feather, a whale’s vertebrae, a lump of coral – O’Connell cast these organic objects in clear resin to give them, like flies trapped for thousands of years in amber, a timeless quality. The resin has no colour, no inclusions or bubbles, yet surrounds the object as if barely there. Part relic and votary, part object of scientific interest, these specimens remain suspended within their clear casting at the point of dissolution and on the brink of decay.

In a culture rife with sluggish melancholy that has lost access to the transpersonal dimensions of existence, Eilís O’Connell’s sculpture touches on the universal need for harmony and transcendence in a largely uncertain and fragmented world.

Sue Hubbard is an award-winning poet, freelance art critic and novelist.