Margaret Egan's landscape paintings and figurative compositions have a shared aesthetic; both are moody, complex and dynamic, writes Gerry Walker.

Margaret Egan casts a wide net in her search for inspirational themes. Her subjects include landscape, still life and figurative painting. She is equally proficient as a sculptor having trained at the National College of Art and design with Breton sculptor Yann Goulet.

Margaret Egan lives in Dublin close by the sea and also enjoys walking in the west coast of Ireland. Both locations feature prominently in the body of her work providing, as they do, a rich source of material for her atmospheric seascapes. It was Picasso who noted that the artist is 'a receptacle for emo tions that come from all over the place, from the sky, from the earth, from a passing shape, from a spider's web'. This is especially apparent in Egan's work. Her land and seascapes are immediate, painterly and gestural in their execution. Her figurative paintings are introspective and contemplative. They work on a different but related level. For Egan, landscapes are like people - moody, complex, dynamic and never finite.

The artist's preferred medium is acrylic on linen. This allows for maximum textural effect and remains a strong characteristic of the work as a whole. While working with oil paint in the past and appreciative of its plasticity, Egan found she had an aversion to some of its malodorous attributes. By mixing structure gell with acrylic, Egan discovered she could achieve similar effects of plasticity.

Egan's working method is relatively straightforward. She sketches briefly whilst on walking expeditions and paints from memory later in the studio. She says that she always prefers to work in this manner, favouring the view, that although memory is not always accurate the feeling is always true.

Technically the images are composed of layerings of paint which are applied with a studied immediacy underpinned by considerable draughts manship. This is shown clearly in Sandymount Strand (Fig 2). The layers are actual and metaphorical. They refer to what she once described as 'the feeling of the landscape, the layers of history, the history of nature itself, with its wonderful raw, sad and sometimes painful excitement'.

In this regard she is aware of similar expressions of roman tic memory in the work of Hughie 0 Donoghue and the poetry of Seamus Heaney. The image of the bog as repository of time, place, history and cultural meaning has particular resonances

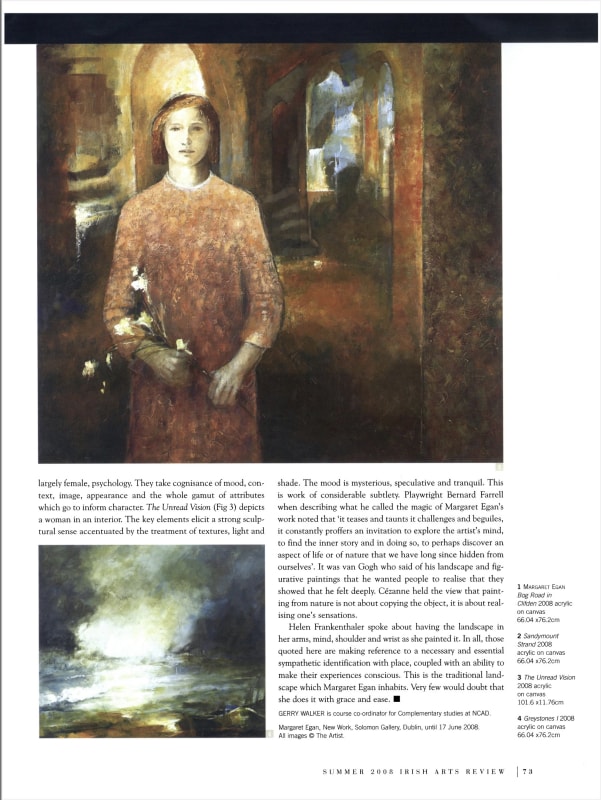

for her as evidenced in Bog Road in Clifden (Fig 1). By contrast, her figurative paintings exhibit a more obviously subdued style but still manage to explore themes already adverted to in the landscapes. They are not portraits within the conventional meaning of the term. They are imaginative compositions reminiscent of a softer version of El Greco or Weimar expressionism, which seek to explore a possibly universal underlying, largely female, psychology. They take cognisance of mood, context, image, appearance and the whole gamut of attributes which go to inform character. The Unread Vision (Fig 3) depicts a woman in an interior. The key elements elicit a strong sculptural sense accentuated by the treatment of textures, light and shade.

The mood is mysterious, speculative and tranquil. This is work of considerable subtlety. Playwright Bernard Farrell when describing what he called the magic of Margaret Egan's work noted that 'it teases and taunts it challenges and beguiles,

it constantly proffers an invitation to explore the artist's mind, to find the inner story and in doing so, to perhaps discover an aspect of life or of nature that we have long since hidden from ourselves'. It was Van Gogh who said of his landscape and figurative paintings that he wanted people to realise that they showed that he felt deeply. Cézanne held the view that painting from nature is not about copying the object, it is about realising one's sensations.

Helen Frankenthaler spoke about having the landscape in her arms, mind, shoulder and wrist as she painted it. In all, those quoted here are making reference to a necessary and essential sympathetic identification with place, coupled with an ability to make their experiences conscious. This is the traditional landscape which Margaret Egan inhabits. Very few would doubt that she does it with grace and ease.

Gerry Walker is course co-ordinator for Complementary studies at NCAD.