When the sculptor asked Sorcha Duggan to pose for the work, she went home and told her boyfriend, who said “No you’re not” – cementing her resolve to do it, she says.

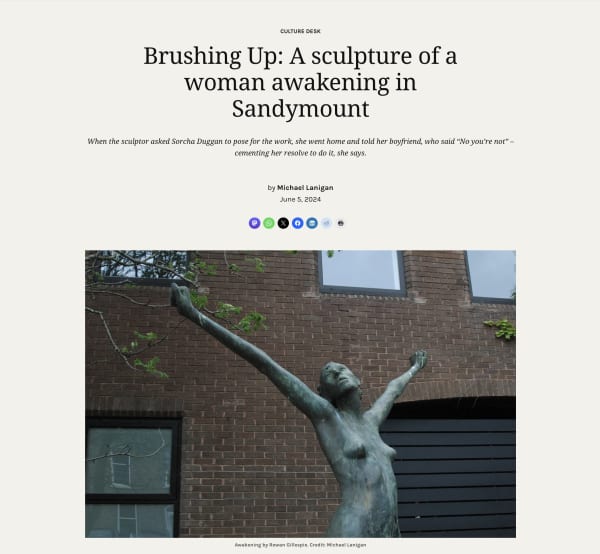

In a modest front garden, just off Sandymount Green stands a patinated blue bronze statue of a woman, nude, her arms cast out as if stretching triumphantly.

Her solemn head is thrown back and she faces up to the sky and the trees beside the driveway of 4 Claremont Road, the Revenue regional office.

Dublin City Council granted permission to sculptor Rowan Gillespie for the landmark in January 1996

Gillespie, a Dublin-born artist, is perhaps best known for “Famine”, the gaunt, hollow-eyed bronze figures that stand on Custom House Quay.

He was also behind “Aspiration”, a nude female figure who scaled the Treasury Building on Grand Canal Street until the property was redeveloped by Google.

She was formerly male, but her gender was changed at the request of developer and Ronan Group Real Estate founder Johnny Ronan, Gillespie says. “He said there’s no way I’m having a naked man climbing up here.”

Unlike the Treasury Building climber, the skyward woman on the Claremont Road often slips under the radar.

“One I often forgot about,” said Gillespie, in an email, confirming it was his work, in late April. His website doesn’t mention it either.

Still, even if overlooked, the piece proved integral to his work from the mid-1990s onward.

Spring, the season, not the Labour leader

Once Gillespie began to think back to when he made the statue, titled “Awakening”, the memories rushed back.

He was in his early forties when he got the commission to create the sculpture at the Revenue office, he said, over the phone one afternoon in late May. “It was a very vague thing with a low budget, just: would I do a sculpture for them?”

He pitched Revenue a working idea, a small sculpture titled “Homage to Spring”, which they assumed was a tribute to Dick Spring, the former Tánaiste and Labour party leader, he says. “What I knew was that I wanted this slight twist in the body, and that was something I did and liked in the ‘Homage to Spring’ sculpture.”

But, he hadn’t gotten a model, he says. That was something he was stewing on, he says, while out dining one day with a couple of artists in Glasthule.

“Then the waitress came over to take the order, and when she started to write in her pad, she sort of stuck her hip out to the side,” says Gillespie, “and I thought, ‘God, she is the person.’”

He asked her right away, he says, laughing. “She looked at me surprised, and said she’d think about it. Everyone at the table said it was the most bizarre thing I did.”

The lost Sorcha Duggan

Rowan Gillespie lost contact with the model who posed for “Awakening” after he had installed the statue in 1996, he says. “Her name was Sorcha Duggan. But I don’t know much more about her.”

Was this the Sorcha Duggan who shows up as the first search result on Google? No, said that Sorcha Duggan. But she does know the model Sorcha Duggan, she said.

They are about the same age, said the first Sorcha Duggan. “In fact, there is more than two of us.”

There are four Sorcha Duggans and they all came into each other’s orbits while exchanging concert tickets several years ago on 26 May, said Sorcha Duggan, the model, on 25 May. “We named it Sorcha Duggan day.”

Sorcha Duggan, the model, was 22 years old when Gillespie approached her. She had never posed before. But she was a dancer, she says. “I had done a lot of contemporary ballet and yoga.”

She knew him and his late wife Hanne Gillespie as regulars in the restaurant where she worked, she says. “I had no idea he was a sculptor.”

His offer startled her, she says. But it was Hanne, who was also present, who ultimately reassured her. “Rowan then wrote me a beautiful handwritten letter with some designs, early drawings of a piece he was working on, ‘Homage to Spring.’”

She considered the offer, she says. “Then, I went home and told my boyfriend, and he said, ‘No, you’re not’, and if there was ever any doubt in my mind now, I was 100 percent going to.”

She sat for Gillespie six or seven times, she says.

Early in the first session, an idea sprang out to Gillespie, he says. “When she came out from behind a little screen to pose, she suddenly jumped out and held her arms out, fists clenched, real defiant ‘Here I am, naked’ and the face with an attitude.”

Thirty years have passed, and not all of the steps are clear in Duggan’s memory, she says. “I remember there was a plaster cast made, and he cast my hands and feet.”

But the feet on the finished statue aren’t hers, she says. “They’re his, because my feet broke off in the plaster stage, and I had gone away for the summer, so he had to cast his own feet.”

An awakening

As he was working on “Awakening”, Gillespie was also creating the Treasury Building “Aspiration”, he says. “I do see the two statues as being related.”

Duggan left a powerful impression on Gillespie, he says, and set off a chain of ideas that led to a series of sculptures that he then proceeded to develop, titled “A Woman”.

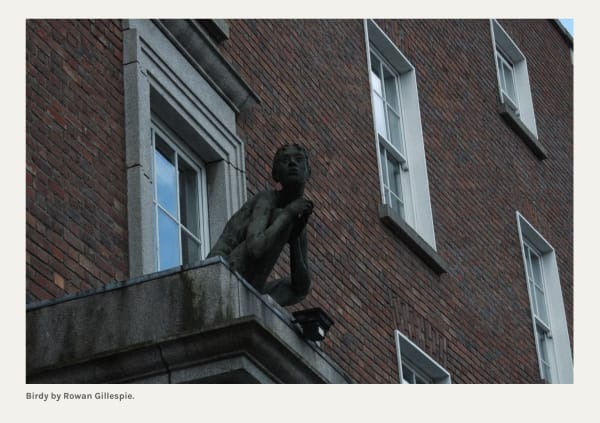

This included the Treasury Building sculpture, and a smaller one, “Birdy”, which sits over the portico of Crescent Hall on Mount Street Crescent, he says.

“That sculpture was the beginning of this, a notion of women finding freedom and liberation, with the final sculptures in the series being flying figures,” he says.

“Awakenings” prompted this narrative of finding one’s confidence, he says. “It was the early expression of that. It was a key one to the whole series.”

That was certainly the impression Gillespie gave when Duggan was posing for him, she says. “He said this was definitely a different route that he was taking. But I often wondered if that was the case.”

It was the fact that she could never find references to “Awakening”, either in the context of “A Woman”, or indeed, on his website, that left Duggan worried he might not have valued it as much, she says. “But now that I know this, obviously I know it’s not the case.”

Ultimately, this was the only time Duggan would pose as a model, she says. “It was a one-off thing, but it was liberating, because a lot of people told me not to do it. There was a stigma then, that you were told this is not what you do.”

She has a picture of it at home. But few people know it’s her, she says. “But I’m glad I did it, and I will tell my daughter about it in the future.”