Peter Murray journeys to sculptor Michael Quane's studio in Cork, which provides an insight into his inspirations and method of working

Michael Quane and his wife, artist Johanna Connor, live in a former church just north of the village of Coachford in Co Cork. The conversion of this 19th-century building into a home, studio and exhibition space has taken years, with much of the work being done by Quane himself. While from an external perspective the building has changed little, it is now surrounded by gravel paths and wildflowers, softening the hard outlines of stone walls and lancet windows.

Inside, wood floors have been laid over Victorian tiles, the walls are insulated and panelled and skylights now flood the building with light. Wooden columns support a mezzanine level that houses a living area and Connor's studio.

Throughout this remarkable building, works by both artists are displayed on white walls or placed on plinths in the exhibition space. The overall effect is practical, efficient and wildly romantic. Respected and protected, the tiled floors, memorial plaques and timber beams are preserved behind the walls and below the floors of what has become a modern, light-filled space.

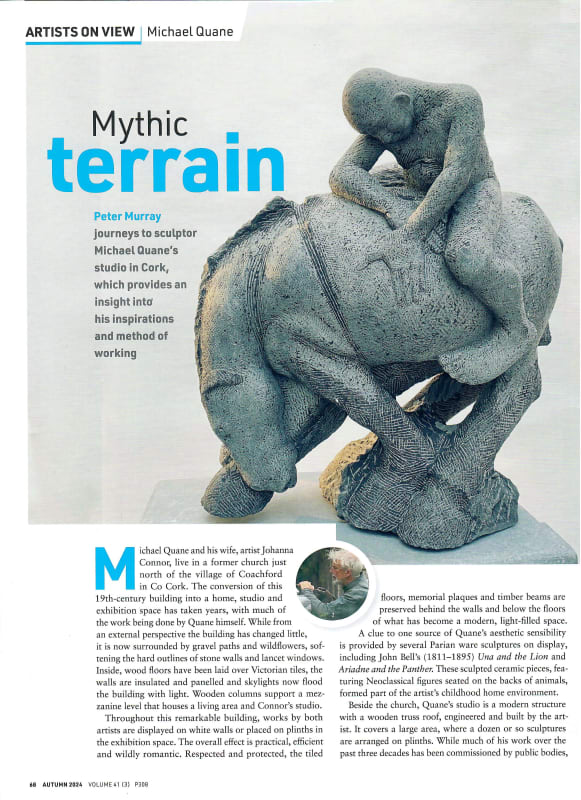

A clue to one source of Quane's aesthetic sensibility is provided by several Parian ware sculptures on display, including John Bell's (1811-1895) Una and the Lion and Ariadne and the Panther. These sculpted ceramic pieces, featuring Neoclassical figures seated on the backs of animals, formed part of the artist's childhood home environment.

Beside the church, Quane's studio is a modern structure with a wooden truss roof, engineered and built by the artist. It covers a large area, where a dozen or so sculptures are arranged on plinths. While much of his work over the past three decades has been commissioned by public bodies, Quane also pursues a consistent studio practice, making smaller works that respond to his own creative impulse and vision. While he has carved Irish limestone for years, many of these newer works are made from white marble block that has been imported from Carrara, and also an Italian stone, Bardiglio. The technical skill that underpins Quane's work is evident throughout: most of the surfaces are rough, still bearing the marks of the com-pressed-air claw chisel he uses to carve out the forms. There is a Mannerist or Baroque quality to Quane's art, perhaps one that relates to the artist's reaction to working in unsettled political times -

‘Strange Beasts' was the title of the exhibition he held in 2020 at the Lavit Gallery in Cork. His sculptures can be read as metaphors, with figures, both animal and human, representing states of being, depicted in the act of turning and twisting, emphasising an energetic, sinewy quality. His human figures cling to animals, full of energy and animation, often on the verge of becoming unbalanced. Featuring mostly horses and riders, the new sculptures do not represent a radical departure in the artist's oeuvre, although they are perhaps more confident, accomplished and playful. Each is on its own plinth and can be read as an individual work of art, but they also form an interrelated series, one that continues to explore the relationship of mankind and nature, a theme that has informed the artist's approach over the past thirty years.

Quane carves by instinct, almost unconsciously, allowing the form to evolve as he proceeds rather than making a precise maquette or model beforehand and translating that into stone. He is equally adept at carving sculptures from small blocks of stone and large ones weighing twenty tons, the upper limit of what can be extracted from a quarry by crane. It is not fanciful to say that Quane works in the tradition of Michelangelo, who also carved white marble from Carraa and regarded his art as liberating forms trapped within the stone. Whether large or small, Quane's sculptures have an independent, self-contained quality, full of tension and dynamic movement, that allows them to be successfully sited in different locations, both indoor and outdoor. His public-art commissions include Fallen Horse and Rider, sited at

Midleton in 1994, Horses and Riders (1995) at the Mallow roundabout and Figure Talking to a Quadruped (1994) in the grounds of University College Cork. These three sculptures form a single body of work, exploring the mythic territory of horse and rider, while his History and a Dustsheet (1996) at Ballincollig roundabout delves into the metaphoric and real, with a figure pulling a dustsheet off a large millwheel.

Works by Quane can also be found at Castleblaney College in Co Monaghan and at Mayorstone Park Garda Station in Limerick, where his Persona (2000) celebrates the ordinary citizens of the state. Located at the Blasket Centre at Dún Chaoin, Islandman (1993) speaks of the people who once lived on the windswept Blasket Islands.

Many of Quane's smaller and medium-sized works form centrepieces and features in gardens and houses, both in Ireland and overseas. With its Classical and Renaissance overtones, mixed with an often Surrealist imaginative flavour, his work has proved popular with collectors, not only in Ireland, but also in England and continental Europe.

Michael Quane

Solomon Fine Art, Dublin

26 September - 19 October.

Peter Murray is a freelance writer, curator and historian and former Director of the Crawford Art Gallery, Cork

MICHAEL QUANE

HORSE WITH A FIGURE, 2023

Chrysalis, limestone

50 × 40 x 30cm

NABRESINA PLAYTIME, 2024

light Nabresina limestone

47 × 24 x 28cm

AG CODLADH, 2023

Honey statuario marble with pointed claw finish

22 × 45 x 24cm

BEACHED, 2024

Honey Statuario

32 × 25 × 23cm