Sunday Independent

JUST SAYING

- excerpts from an interview with Emily Hourican.

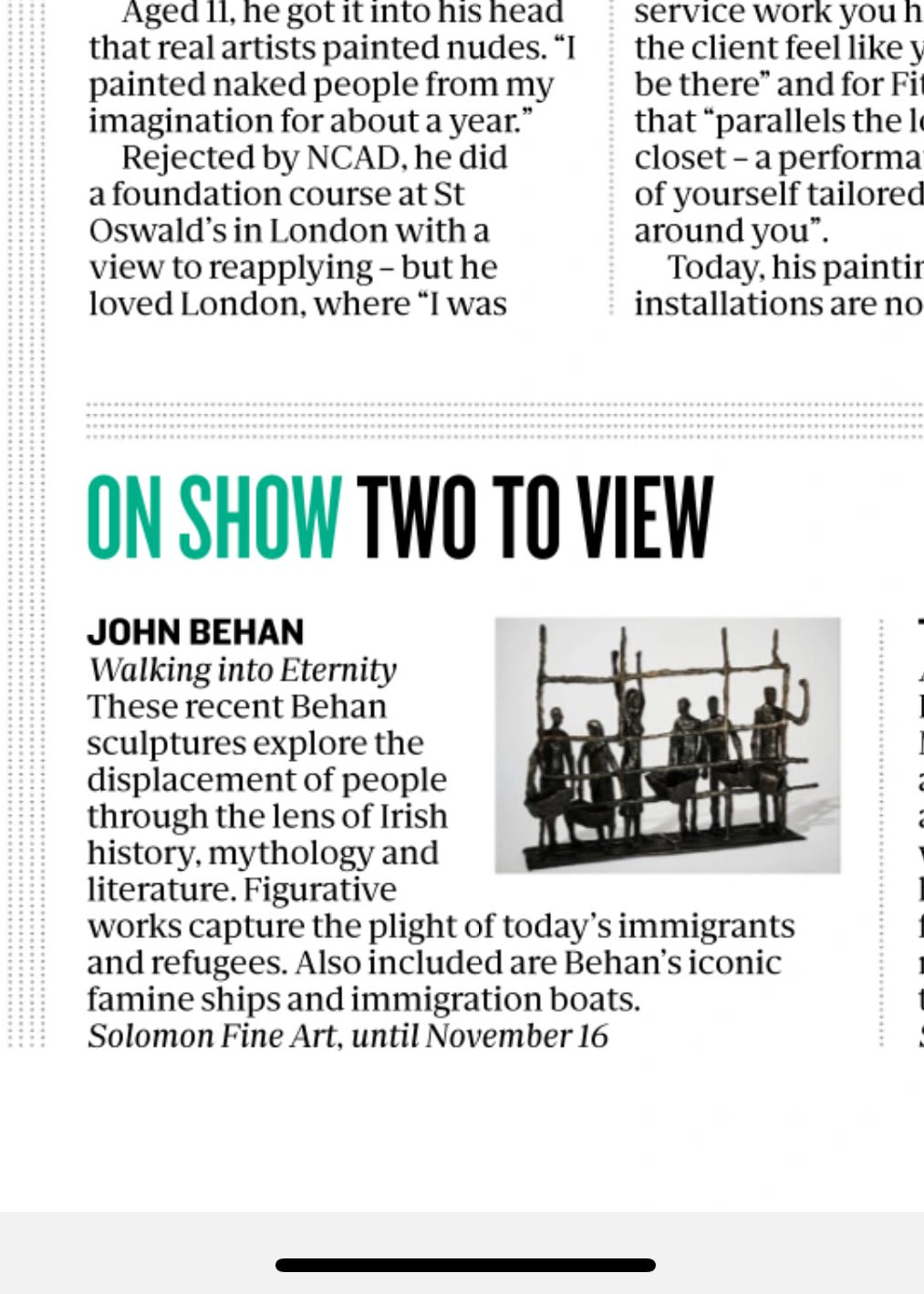

John Behan RHA (85) is an award-winning sculptor and helped establish the Project Arts Centre in Dublin in 1967. He was born on Sheriff Street, and lives in Galway.

Sheriff Street was a lovely community, but in the 1950s many people emigrated.They went to England. The destruction of that – your psyche is gone, the social structures are gone, families torn apart.

Since I was a small kid, I always wanted to do something with my hands. Paint things, make things – and that’s still as strong as it was when I was four and five years old. It hasn’t gone away.

I left school as soon as I could. One thing you can say for the Christian Brothers – and I didn’t get on well with them, I got out of that as soon as I could – but they taught us [about] the poets: Yeats, Shakespeare, Wordsworth. We got all of that at eight or nine years of age and that stuck with me all my life.

Patrick Kavanagh was who I read, because he was accessible. He was in the pub when I’d go in there. I’d go in on my own after work as an apprentice and there was Kavanagh sitting there, muttering away to himself. Because by that stage – about six o’clock in the evening – he was gone in drink, as they say.

I was commissioned by the government to create a National Famine Memorial in the mid-1990s. I sculpted a coffin ship that stands at Murrisk Millennium Peace Park. At that time, the Famine was too painful, too recent in people’s memories, family memories. People eating grass by the sides of the road, starving to death, the Famine ships – a lot of them perished on the way over, from sickness, disease. Nothing has changed in the way people have to suffer migration, and what happens to them.

Photo: Mark Condren

I’ve been very lucky with my health. My grandfather – John Behan was his name as well – he was a tough old guy. A survivor. Born in 1852, the last year, officially, of the famine. I knew him well, he was nearly 100 when he died. They were long livers.

I’m just fortunate, so far so good. I don’t worry about it too much because if you do, you get into a knot. You don’t do yourself any good. I just wake up every day and do the best I can. That’s the way I see it.

It takes a long time for some artists to get around to what their real objective is.That is in terms of what areas they want to explore. I needed to live. You get people like Dylan Thomas and all the work is done by the age of 30, they can’t add anything to that. I was only beginning at that stage.

I had a fire in my studio in Galway recently. That was horrible. I’m only getting back to anything like normal now. I’ve been out of the house for 14 months, trying to rebuild. I’d no studio to work in. I had to go up to Mayo, driving up and back, just for a day’s work, doing that for a full year. It was strenuous, but I wanted to do it. I don’t complain. I don’t moan about it, because there’s no point.

In the last few years, I’ve been going to Greece and volunteering at the camps where migrants are held, running art classes. I felt their pain and that’s why I did it. I’m not trying to change the world, I know I can’t. I’ve no power – and it’s all to do with power. This is all I can do really. I try and avoid getting too much involved in the politics.

The Christian Brothers weren’t all vicious and savage. But some of them were – and there were paedophiles, all kinds of terrible things went on there, life-denying things, destructive. The psychological destruction was terrible, and it destroyed some people. There were people who, the day they got out of school, went abroad and never came back. They couldn’t take Ireland at all. You met them in London, you met them all over the place. They were destroyed.

There’s a lot of money in Ireland now. And still a lot of poverty. Whole groups of people haven’t changed – their social situation is the same as it was in the 1950s. They’re poverty-stricken, they’re criminalised, they’re stuck in a rut. And they were the people who were always ignored.

You can’t have great art happening at the same time as selfishness in society. It doesn’t work. There’s a paradox: the same money that supports art and artists, is the money that brings smugness.

John Behan RHA ‘Walking into Eternity’ continues at the Solomon Gallery until November 16; solomonfineart.ie. A film of Behan’s life, ‘Odyssey,’ by Donald Taylor Black, will be screened there on November 10 at 4pm

John’s exhibition also gets a recommendation from Niall MacMonagle in the Indo’s visual arts ‘What Lies Beneath’ column.