I don't give a damn what age I am, I want to do this...'

As he approaches 80, sculptor John Behan is busier than ever. A new show, a sculpture of Arkle, and work in a refugee camp in Greece all keep him busy, writes Emily Hourican

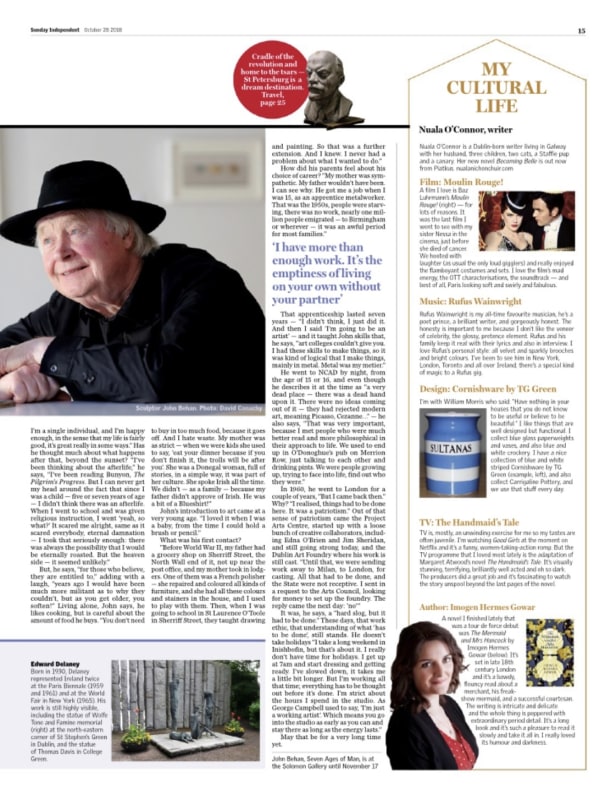

SCULPTOR JOHN BEHAN. PHOTO: DAVID CONACHY

If, as George Orwell believed, we all have the face we deserve at 50, how much more is that true when we reach 80? The face that sculptor John Behan, who will be 80 on November 17, turns on the world seems decades younger; open, curious, almost seraphic except for the hint of mischief, with a pair of sharp blue eyes and a shock of soft white hair. Certainly, it is not the face of someone looking to take life easy.

"I'm as busy as a little bee,” he tells me over lunch. As well as the solo exhibition, Seven Ages of Man, currently at the Solomon Gallery, John is working on a life-size statue of the legendary racehorse Arkle — built from the bones up, based on Arkle's skeleton which is in the Irish National Stud museum in Co Kildare — for Galway Racecourse. And, in his spare time — such as that is — he is travelling to and from Greece, where he is working with migrants in a camp outside Athens. "At this moment in time I probably am too busy, but no, I manage.”

Of the Greek odyssey, he says: "It's my own idea. I'd been working on this idea of immigrants for a long time” — it's a theme that surfaces in his work again and again; one of his most significant pieces, Arrival, a Famine ship, was a gift to the UN from the Irish government, and stands outside the UN HQ in New York; it is where Varadkar, along with Bono, recently launched Ireland's bid for a place on the UN Security Council — "but I'd never met any. So I said, I'm going to get off my butt and go out here and meet some real people.”

How did he go about it? "I just went to the Irish embassy in Athens. The Irish government has always talked about how important culture is in Irish society so I said, 'I'm going to try this, find out if there's any truth in this…' That was part of it. It was my own personal thing — to see if this portrayal of Ireland as a cultural country supported by the government, was an actual fact or was it just propaganda?” (There's John's mischievous side at work). "So I went and I said, 'this is who I am, and I want to meet some refugees'. And, he says: "It all worked out very nicely. I found the ambassador and her staff were most helpful.”

The camp John has been visiting, Eleonas, is around 12 miles outside Athens and is, he says, "not a decrepit place, it's a very well-run place. They are well looked after. I was shown maybe the best of things — I wouldn't say that what I was seeing was the absolute truth of things, but I did meet people who are real refugees — not just bright people set out in front so they make a good impression. I spoke to the people themselves, and started doing very basic teaching, making pictures and drawings, with a project in mind — to erect a big boat, depicting their flight, and how close it was, in my estimation, to the Irish situation during the Famine. People trying to flee their country because there was no sustenance for them. Drowning in their thousands — the same things happened to our ancestors on the way to America, they got within sight of shore and a storm came up and the people were lost at sea. It's the same thing.”

It was not, he says, "what you would call a happy experience, but it was a good, positive experience for me.” The plan, he says, is to work with Bill Shipsey, from Waterford and founder of Art for Amnesty, and make a large piece of work representing the experiences of the refugees in the camp, built with them, and get a site in Athens to display it.

Did he ever think he would be doing this, working like this, at 80? "I didn't think about age,” he says. "I said, 'I don't give a damn what age I am, I want to do this'. And I really don't think of myself as… as long as I can move around without discomfort, and I can, then it's OK. I didn't think I'd get here, to 80. I just took life as it came. Philosophically speaking, I was an existentialist by the time I was 30, and that philosophy means you take what's there in front of you and you deal with it on a daily basis. That's the way I interpreted it anyway.”

And his energy is undiminished? "I hope so,” he laughs, then stresses: "For me, doing this is a very positive thing. It's not an ego trip; I don't want to be part of anything like that. Who would go all the way to Greece for an ego trip?” he laughs, adding, "You'd get one closer to home!”

If you're John Behan, you certainly would. He is among the best-known and most respected artists working today, with pieces in the National Gallery, the Hugh Lane, the Crawford, and collected by Mary McAleese, Mary Robinson, Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands and Bill and Hillary Clinton. And yet, when I ask is he happy, he says with complete candour: "I wouldn't call it happiness, though there is a certain fulfilment.”

John's partner, Dr Emer MacHale, died just over five years ago, and the tragedy of that loss is still with him.

"To lose your life partner — which Emer was... I miss Emer an awful lot, but there's nothing much I can do except honour her memory. You can't bring people back. A life that ends too soon — it's their loss, it's not your loss. If you consider it logically, it was their life, and it's grossly unfair to them, first and foremost. I have more than enough work,” he says, "it's the emptiness of living on your own without your partner. It's as simple as that.

John, who married and had three children before separating, and meeting Emer in 1987, lives alone now. "I haven't any new relationship,” he says, "I'm working on my own now, I'm a single individual, and I'm happy enough, in the sense that my life is fairly good, it's great really in some ways.” Has he thought much about what happens after that, beyond the sunset? "I've been thinking about the afterlife,” he says, "I've been reading Bunyon, The Pilgrim's Progress. But I can never get my head around the fact that since I was a child — five or seven years of age — I didn't think there was an afterlife. When I went to school and was given religious instruction, I went 'yeah, so what?' It scared me alright, same as it scared everybody, eternal damnation — I took that seriously enough: there was always the possibility that I would be eternally roasted. But the heaven side — it seemed unlikely.”

But, he says, "for those who believe, they are entitled to,” adding with a laugh, "years ago I would have been much more militant as to why they couldn't, but as you get older, you soften!” Living alone, John says, he likes cooking, but is careful about the amount of food he buys. "You don't need to buy in too much food, because it goes off. And I hate waste. My mother was as strict — when we were kids she used to say, 'eat your dinner because if you don't finish it, the trolls will be after you'. She was a Donegal woman, full of stories, in a simple way, it was part of her culture. She spoke Irish all the time. We didn't — as a family — because my father didn't approve of Irish. He was a bit of a Blueshirt!”

John's introduction to art came at a very young age. "I loved it when I was a baby, from the time I could hold a brush or pencil.” What was his first contact? "Before World War II, my father had a grocery shop on Sherriff Street, the North Wall end of it, not up near the post office, and my mother took in lodgers. One of them was a French polisher — she repaired and coloured all kinds of furniture, and she had all these colours and stainers in the house, and I used to play with them. Then, when I was going to school in St Laurence O'Toole in Sherriff Street, they taught drawing and painting. So that was a further extension. And I knew. I never had a problem about what I wanted to do.”

How did his parents feel about his choice of career? "My mother was sympathetic. My father wouldn't have been. I can see why. He got me a job when I was 15, as an apprentice metalworker. That was the 1950s, people were starving, there was no work, nearly one million people emigrated — to Birmingham or wherever — it was an awful period for most families.”

That apprenticeship lasted seven years — "I didn't think, I just did it. And then I said 'I'm going to be an artist' — and it taught John skills that, he says, "art colleges couldn't give you. I had these skills to make things, so it was kind of logical that I make things, mainly in metal. Metal was my metier.”

He went to NCAD by night, from the age of 15 or 16, and even though he describes it at the time as "a very dead place — there was a dead hand upon it. There were no ideas coming out of it — they had rejected modern art, meaning Picasso, Cezanne…” — he also says, "That was very important, because I met people who were much better read and more philosophical in their approach to life. We used to end up in O'Donoghue's pub on Merrion Row, just talking to each other and drinking pints. We were people growing up, trying to face into life, find out who they were.”

In 1960, he went to London for a couple of years, "But I came back then.” Why? "I realised, things had to be done here. It was a patriotism.” Out of that sense of patriotism came the Project Arts Centre, started up with a loose bunch of creative collaborators, including Edna O'Brien and Jim Sheridan, and still going strong today, and the Dublin Art Foundry where his work is still cast. "Until that, we were sending work away to Milan, to London, for casting. All that had to be done, and the State were not receptive. I sent in a request to the Arts Council, looking for money to set up the foundry. The reply came the next day: 'no'”. It was, he says, a "hard slog, but it had to be done.” These days, that work ethic, that understanding of what 'has to be done', still stands. He doesn't take holidays "I take a long weekend in Inishbofin, but that's about it. I really don't have time for holidays. I get up at 7am and start dressing and getting ready. I've slowed down, it takes me a little bit longer. But I'm working all that time; everything has to be thought out before it's done. I'm strict about the hours I spend in the studio. As George Campbell used to say, 'I'm just a working artist'. Which means you go into the studio as early as you can and stay there as long as the energy lasts.”

May that be for a very long time yet.

John Behan, Seven Ages of Man, is at the Solomon Gallery until November 17